The Enduring Legacy of Classical Crowd Theory

Throughout the 19th century several contributions were made to the study of crowd behaviour. This body of work, now commonly referred to as Classical Crowd Theory, had a profound impact on public policy across the world, shaping how governments and law enforcement agencies approached crowd management and public order for much of the 19th and 20th centuries.

It is suggested the enduring legacy has in fact impeded effective crowd management and led to inefficient, suppressive and even inflammatory tactics and techniques.

The influence of Classical Theory continues to echo in both public policy and popular understanding

Classical crowd theorists include;

Gustav Le Bon (1841–1931)

Key Work: The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895)

Le Bon is perhaps the most prominent and influential classical crowd theorist. He proposed that individuals in crowds lose their sense of personal responsibility and rationality, becoming more suggestible, emotional, and impulsive. Le Bon suggests a loss of standards, an incapacity to think coherently and a reversion to a more primitive form. His work is often seen as the foundation of classical crowd theory, characterising crowds as inherently irrational and dangerous. Le Bon explains these behaviours as a “contagion”, a disease like spread throughout crowd members. His theory is based on the premise that mere presence in a group results in rapid and uncontrollable submergence and subsequent, inevitable deterioration in standards of behaviour.

Gabriel Tarde (1843 - 1904)

Key Work: Laws of Imitation (1890)

Tarde suggested that crowds are shaped by imitation rather than irrational impulses. He argued that crowd behaviour spreads through suggestion and imitation, rather than the disease like contagion suggested by Le Bon. However, Tarde’s work, in similar fashion to his contemporary, proposed a mindless nature whereby crowds senselessly mimic the behaviour of others.

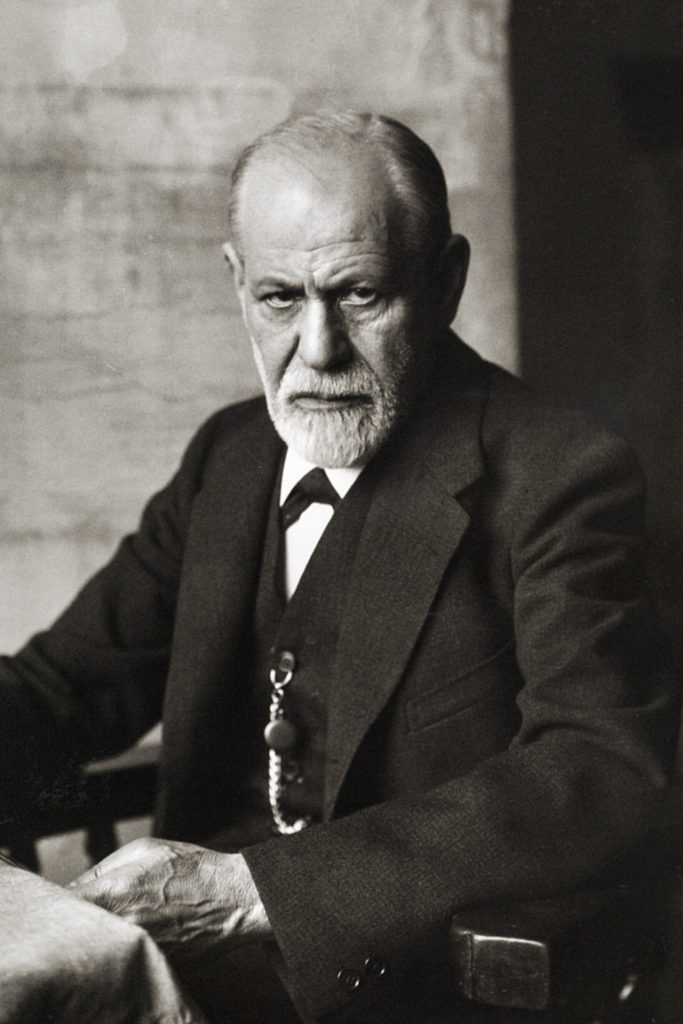

Sigmund Freud (1856 - 1939)

Key Work: Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921)

Freud expanded on Le Bon’s ideas, focusing on the emotional ties that bind individuals in crowds. He suggested that individuals in crowds substitute the authority of the group leader for their own ego, leading to a loss of personal autonomy. His psychoanalytic approach promulgated the emotional and unconscious dimensions of group behaviour.

Wilfred Trotter (1872 - 1939)

Key Work: Laws of Instincts of the herd in Peace and War (1916)

Trotter viewed crowds through a biological and psychological lens, likening group behaviour to herd instincts. He argued that humans have innate tendencies to conform to group norms, and that crowd behaviour can be understood as an extension of this instinctual conformity.

Charles Mackay (1814 - 1889)

Key Work: Laws Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1841)

Mackay’s work, though predating Le Bon, was an early exploration of how irrational behaviour spreads in crowds. He focused on collective delusions, financial bubbles, and mass hysteria, illustrating how otherwise rational individuals can participate in irrational group behaviours when swept up by collective emotions.

Classical crowd theorists collectively laid the foundation for how crowds were perceived in the early 20th century, often emphasising irrationality, contagion, and loss of individuality in collective settings. As social scientist and crowd behavioural expert Stephen Reicher points out, Le Bon’s seminal work – The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895) has been described as the most influential psychology text of all time. This is further supported by the subsequent significant influence on public policy and crowd control measures, often justifying more repressive approaches to crowd management. An accepted hypothesis of irrationality and inevitably poor behaviour legitimises, in fact requires, an authoritative, suppressive response.

The legacy of Classical Crowd Theory still lingers, particularly in how public authorities and media portray crowds. The idea that crowds are dangerous, unpredictable, and prone to violence continues to shape crowd management approaches in many parts of the world.

Classical crowd theory’s emphasis on the uncontrollable, emotional nature of crowds leads to policies that prioritise control and containment rather than negotiation or engagement. These assumptions frequently lack any evidential base and the continual desire to control and contain such groups requires significant resource at notable cost. Measures often involve creating physical barriers, cordons, and designated zones to restrict crowd activity. Such techniques are common across a wide range of crowded events. The distrust and perceived threat encourages authorities, security companies, event organisers and police forces to implement levels of control and proactive contingencies to prevent the expected disorderly actions.

Classical crowd theory suggests a clear division between the individual and the crowd, claiming individuals are stripped of their rationality and morals. This leads to an ‘us vs. them’ mentality in crowd management policies, where authorities view crowds as a threat and an ‘out group’ that need to be controlled. Interestingly, as Stephen Reicher points out, those responsible for proposing classical theory did so from a position outside the crowd. Research was conducted looking from an ’out group’ perspective and therefore it is unsurprising the subsequent theories failed to consider the nuanced nature of intergroup relationships and social identities at play.

Management strategies thus become adversarial, with a focus on treating crowds as hostile entities. As such negotiation or communication between those in authority and crowd members is minimal or non-existent. Instead, an emphasis on confrontation and dispersal ensues, contributing to an antagonistic relationship between those charged with managing crowds and the large gatherings of people themselves

Classical assumptions have also had a notable impact on the management of sports crowds, particularly football matches in Europe. The fear that large gatherings of sports fans could devolve into riots led to the implementation of heavy policing at stadiums where football hooliganism became a major concern (Football policing costs in the UK alone are reported to be around £48 million a year). The assumption that crowds of fans could easily become violent encouraged the development of crowd control measures that emphasised containment and control. This continues to be seen across numerous footballing events every weekend. A classical approach is perhaps more evident at European football events, than with any other types of gathering. Such crowds are distrusted; inflated perceptions of associated risk often lack an appropriate evidence base, but nonetheless see significant police and security resources deployed.

Influence on public policy is not only visible in terms of policing strategies but also in the broader context of political and social control. The fear of mob violence is frequently used to justify authoritarian responses to protests and demands for social change. There are numerous examples of authorities across the world using repressive measures in response to large-scale gatherings, justified by the belief that the irrational nature of crowds could lead to widespread violence and disorder.

Classical crowd theory continued to dominate public policy throughout most of the 20th century. Two notable points likely featured in maintaining the status quo. Firstly, classical theory assumptions can readily reflect self-fulfilling prophecy. Assumptions of crowd disorder and a distrust of large gatherings, as discussed above, are frequently met with robust control strategies. Such tactics (as detailed in the ‘Social Identity Model’ article on this website) can foster an environment for confrontation. Any subsequent disorder, in the minds of the authorities, serves to justify the initial assumption and subsequent actions taken, reinforcing the cognitive bias and further consolidating the views of the ‘out-group’. This cycle has been witnessed numerous times during the author’s policing and crowd management career.

Secondly, the faceless nature of crowds results in an inability to defend themselves against classical assumptions. Those in positions of authority are able to evade accountability, often leading to the blame being unfairly placed on the crowd rather than on inadequate safety measures or poor planning. Individuals within the crowd do not have a platform to explain their actions or critique the environment in which they were placed. In contrast, those in authority can rely on classical crowd theory narratives to justify their actions, claiming that the crowd’s behaviour was unpredictable and beyond control. By framing the crowd as the problem, those responsible for crowd safety are able to deflect blame, reinforcing the cognitive bias at play. Frequently and repeatedly the crowd themselves are blamed for disasters around the world.

While classical crowd theory dominated public policy across Europe for much of the late 19th and 20th centuries, the mid-20th century saw a gradual shift in academia away from these ideas as modern crowd psychology emerged as a discipline. Classical crowd theory was viewed as simplistic and deterministic in its portrayal of crowds, and social psychologists such as Stephen Reicher, Clifford Stott and John Drury began to promote more nuanced and evidence-based approaches to crowd management.

Extensive and conclusive research from such well renowned academics supports the move away from classical thinking towards a Social Identity approach, whereby crowd behaviour and interactions are viewed from within the group and are explained through shifts, rather than complete loss, of identity.

Subsequent initiatives and projects promote dialogue with crowds and broader understanding of the social and psychological context in which crowds gather and behave (as detailed in the ‘Social Identity Model’ article on this website).

Despite the academic advances, the impact of classical theory continues to be seen. Whilst the extensive work of social scientists clearly evidences the need for improved understanding of crowds, far too often echoes of Le Bon are heard and crowd control measures are implemented which create the very conditions they are designed to prevent. The legacy of classical crowd theory remains in both public perception and some areas of crowd management practice.

The advances made through Social Identity Theory and crowd science are slowly influencing policy, but more work is needed to fully integrate these modern understandings into everyday practices, particularly in large-scale event management, policing, and urban planning.

The persistence of classical ideas in certain areas highlights the need for ongoing education, training, and reform in crowd management practices. By continuing to challenge outdated assumptions and applying evidence based research, we can move beyond the limitations of classical theory and create safer, more effective approaches to crowd management in the future. Crowds are not inherently dangerous, and by understanding their social dynamics, we can create environments that foster cooperation and minimise conflict, ultimately leading to better outcomes for both crowds and those responsible for their safety

Stephen Reicher highlights a quote from historian William Reddy which helps to highlight, and perhaps suggest, a key starting point;

“…the targets of crowds glitter in the eye of history”

Whether we agree with how various crowds behave or not, if we want to develop our understanding then we would gain much by adopting their viewpoint – observe from within the ‘in group’ rather than as a disgruntled outsider.

Understanding crowd behaviour is one of the key modules provided in our accredited training course. Please contact us for more information