Modelling to Improve Crowd Safety

Understanding crowd movement and behaviour is a complex skill which, when inappropriately applied, can have catastrophic consequences. As Still and Pelling (2009) point out, this understanding and application must not be left to chance and indeed, crowd science as a discipline has gathered momentum over recent years. It is suggested the use of models is fundamental in ensuring crowd safety. Crowds are unpredictable and unforeseen accidents may be unavoidable, but they should not be as a result of insufficient, ill thought out plans or a broad brush, incompetent approach. Application of tried and tested tools and models provide a ‘solid, worked through, defendable position’ (Still 2004: 136). When used correctly these tools allow for foreseeable issues to be addressed, managed and controlled, therefore improving safety and mitigating against major incidents. As Still and Pelling assert, ‘crowd dynamics is rooted in maths–in numbers, geometry and modelling’, therefore a crowd management plan that does not utilise available tools is likely to be unfit for purpose.

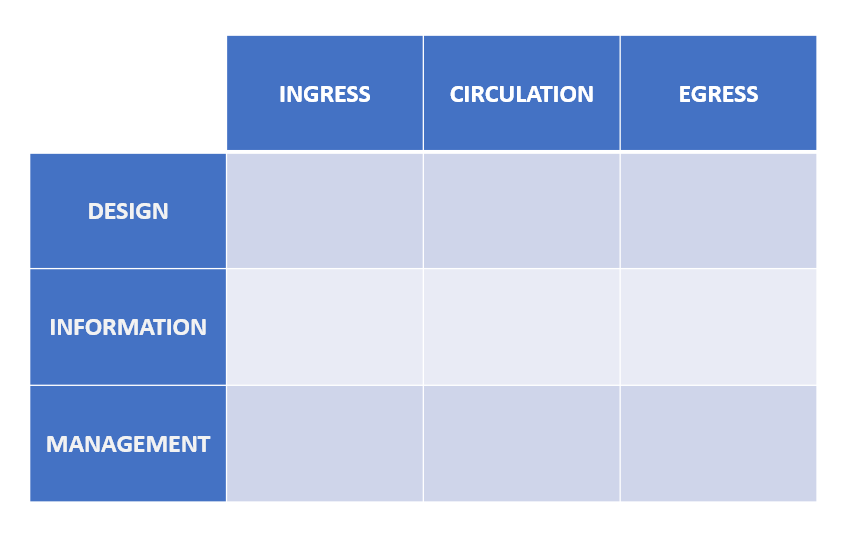

Planning tools such as DIM-ICE and RAMP Analysis (Still 2004) are key elements in the planning phase and should be supported and enhanced with real time decision support tools. Models should not only be used in preparing for an event but also during the event itself to aid crowd managers. Gonzalez (2004) makes the important point that dynamic decision-making is a complex skill, which requires multiple, interdependent, time critical actions, therefore, the use of control room tools and models to aid this process should become common-place.

The screening and searching of fans and customers entering event venues is an area that could benefit from such an approach. The current practice sees event safety officers make professional judgements, often whilst under pressure, around search policies, which are generally based on experience and predictions (Houghton 2021). Guidance is limited and it is suggested an effective tool could be applied to provide crowd managers with assistance in decision making in relation to search procedures.

It is argued an over reliance on experience and feedback provides limited assistance in a fast moving real time environment, whilst the use of tools and models allows for a feed forward approach, and the ability to address issues before they occur. The suggested tool will allow crowd managers to accurately predict the impact of various screening options and provide an evidence based position for a change in policy during an event

Crowded environments are complicated. They present a multitude of potential outcomes, scenarios and even on occasion, disasters. Models and tools allow crowd managers to simplify complex situations, make them easier to interpret and provide a feed forward environment. Human behaviour is difficult to predict and whilst the risks to a crowd cannot always be predicted, every effort should be taken, and every appropriate tool utilised to prevent disaster. Models and tools in the planning phase are becoming more commonplace, with Still’s DIM-ICE matrix in particular, now a staple on most event training courses. However, this practice should be extended to support crowd managers during the event. Current practice tends to rely on a feedback approach whereby success is measured after the decision making process and future decisions are then based around experience.

It is suggested there are clear issues with such an approach as highlighted by Brehmer (1992) and Gonzalez (2004). If the event passes off without major incident, the control room decisions are not questioned and the need for an alternative strategy is not uncovered. The possibility for doing better remains undetected and potentially inappropriate decisions are assumed sound (through the feedback loop) and therefore reaffirmed in the mind of the decision maker.

Research has shown that individuals do not accurately account for the impact their decisions have, therefore the self-feedback is likely to be inaccurate. (Gonzalez 2004). Furthermore, this method requires crowd managers to deal with incidents as they begin to occur. Sudden and catastrophic changes in state are often features in crowd disaster and decision making in this environment is very difficult and stressful (Brehmer 1992, Gonzalez 2004). The use of models develops a feed forward approach whereby problems can be more readily predicted and disaster more likely avoided. The root of the issue, the point at which the crowd risk altered from the plan, can be identified when there is a model or a tool to compare what is expected to happen to what is actually happening. Clearly, this allows for the appropriate causes to be addressed and improvements to be made whereas simply focussing on the catastrophic element of any incident will likely identify the crowd as the culprit, limiting the ability to address the actual causes and failing to prevent repeated issues

Dynamic decision making in a stressful environment, relying on past experience and predictions will inevitably lead to errors. As Brehmer points out, ‘the world will never stop and wait for him to make his decisions’ (1992: 263). The amount of time and pressure a crowd manager has is likely to impact on the effectiveness of decisions (Gonzalez 2004). In order to achieve optimality all relevant, available tools and models should be used by crowd managers in pursuance of crowd safety.

The Need for the Suggested Tool

Searching and screening at events sees a wide range of approaches. Like with much of the industry, there is no specific guidance and references are often vague, advisory and optional. Moreover, like much of the industry, the changes in advice and guidance often come after a significant incident; they are reactive rather than proactive. Following the attack at the Stade de France in 2015, Cleland and Cashmore claimed the security at sports stadia would be

changed forever (2018). Subsequently, the latest edition of the Guide to Safety at Sports Grounds (The Green Guide), included a brief section on searching and screening as follows;

“An example of how a counter terrorism plan might be graduated according to the threat level is the screening or searching of spectators prior to entry. The higher the level of threat, the more through the screening or searching regime is likely to be.” (2018 p. 50)

The Green Guide is the key publication in sports stadium safety. The inclusion of words such as ‘example’, ‘might’ and ‘likely to be’, leave crowd managers to interpret the guidance and adopt the approach they deem fit. Naturally, the crowd manager will rely on their experience and feedback to inform decisions. It is suggested this process could be significantly aided with the use of a real time tool. The current decisions around searching and screening do not follow a regular pattern and often appear sporadic (Darbyshire 2021). At football fixtures, the most commonly adopted process is to apply a targeted search policy for away fans, with less focus on the home fans (Houghton 2021). Whilst this may follow some logic and anecdotal evidence in terms of away fans being more likely to commit low-level football related offences and cause alcohol related issues, this is not the case in relation to significant security threats (Houghton 2021). The Green Guide, the CPNI and UEFA, amongst many others, discuss searching and screening in relation to increased security threat and terrorist activity. (SGSA 2018, CPNI 2021, UEFA 2019).

Therefore, the currently adopted methodologies do not mirror the apparent reasons for the guidance. Furthermore, the decisions to start and stop search regimes appear somewhat ad hoc and are based as much around the need to get supporters into the stadium before kick off as they are on safety and security measures (Houghton 2021, Dickerson 2021). At a local Football Club the stewards are tasked with determining the search requirements, at a nearby festival the festival director sets the searching levels and at an International Cricket venue there is a standard bag search policy. The author has been unable to find a standard approach based on a mathematical model, which supports crowd managers in making evidence based decisions to enhance safety and security.

Using the Suggested Tool

In support of crowd managers, the suggested model is designed to foresee issues and provide decision makers with an accurate picture of how crowds will develop based on screening options. Still (2014) provides a sound basis for this approach,

‘When the control room have a clear idea about crowd arrival, they can monitor the situation and then be in a position to act quickly if there are significant changes form the plan… Without a background model, the risks may pass unnoticed and develop into an incident.’ (p. 204)

Available guidance does acknowledge the impact searching and screening can have on the crowd ingress and flow rate (SGSA 2018). Ironically, the desire to enhance safety and security can in fact achieve the exact opposite and ‘a poorly managed search operation can have a direct impact on crowding outside the ground’ (SGSA, 2018). As well as the potential crowd density issues, the large crowd outside the stadia could also be an attractive terrorist target. This further highlights the importance of appropriate planning and decision making to effectively manage event ingress with policy decisions made on evidence-based formulae. Responding to overcrowding and adjusting plans once issues arise is an unacceptable method of crowd management.

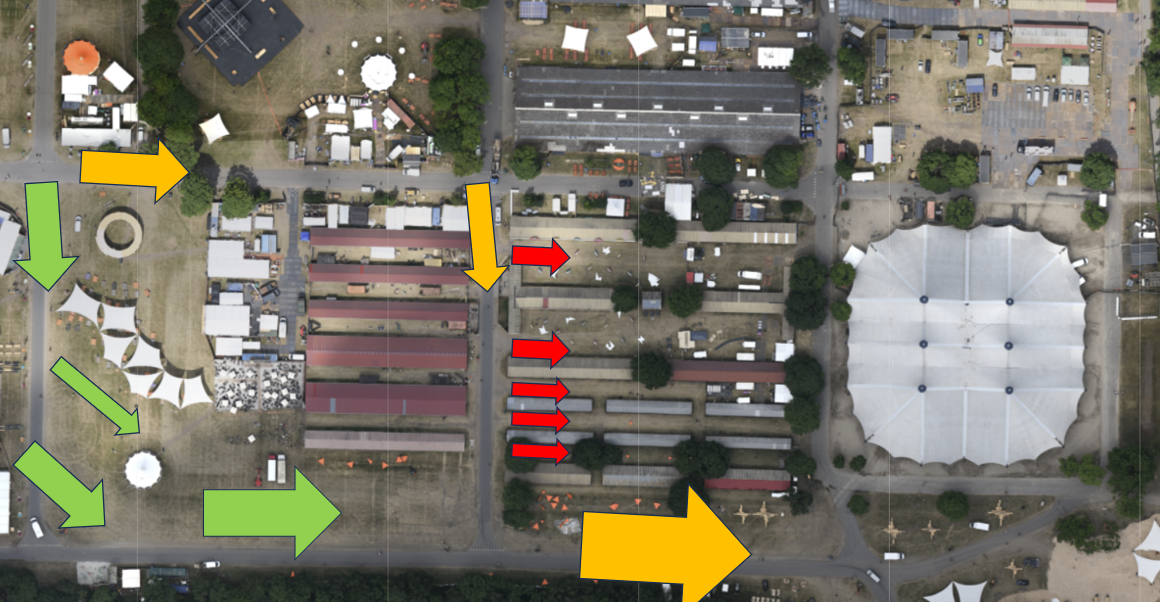

As previously mentioned, a feed forward strategy is preferred. The author’s model requires an accurate arrival profile for the event in question. The example provided is based on a football stadium, and approximates fan behaviour. Once the arrival profile has been established this will form a basis for comparison and allow crowd managers to understand the ingress at their event

The interface provides a straightforward tool to input real time data, which will automatically be compared to the expected arrival profile. The planning interface allows various screening strategies to be input and their subsequent impact on flow rates and ingress effectively managed. The prototype attached provides three different search policies, each with an assumed screening time. Whilst there is currently limited data available on which to base these figures, The Green Guide (SGSA, 2018) and 8 McQuade (2017) provide figures as a basis depending on the type of search carried out.

It is suggested crowd managers carry out their own calculations to more accurately predict the timings for their particular event. The three options available in the current model are ‘no search’ with a screening time of 5.45 seconds, ‘standard search’ with a screening time of 20 seconds and ‘assisted search’, which has a screening time of 10 seconds. These figures are readily adjustable to reflect the screening options available at any event. The tool output allows crowd managers to make informed decisions regarding the strategy they employ. Furthermore, the accepted queue level can be included and an indication provided of when this level will be exceeded. The detailed formulae and arrangement of the interface provides a simple, user-friendly tool, which can be readily adapted to suit any event

For example, if the decision maker chooses a full search policy, the tool will show at what point an unacceptable queue will form. It will then be indicated at what point a change in policy will be required, or when extra staff will be needed to assist in increasing the flow rate. The interface will also show how the current event compares to the expected arrival rate. This information allows appropriate decision making to be made before a potential issue arises and helps to avoid high-pressure situations in the control room. The suggested model provides the crowd manager with evidence on which to base decisions and assess risk. Feed forward rather than trying to close the barn door after the horse has bolted.

In Conclusion...

The many crowd disasters in recent decades and the number of deaths and serious injuries highlight the complexity and difficulty in managing large crowds of people. The nature of such incidents and the often catastrophic surge from manageable to unmanageable suggests a reliance on feedback is completely inappropriate. Addressing issues as they arise, relying on experience and failing to accurately note the impact of decision-making, combine to provide a potentially dangerous environment. Tools and models can assist. The suggested model provides a mathematical, evidence based approach to search policy and, when used appropriately, can accurately foresee potential issues. Contrary to the common saying, in this instance, a good workman can blame his lack of tools

If you are interested in the author’s recent model described in this article, please get in touch. It aims to assist in the ingress phase of any event.