Blaming the Crowd Inhibits Learning

In 2009 The Cabinet Office deemed the examining of past incidents as ‘crucial’ to identify lessons for future events. It is suggested, however, that despite the many opportunities to review and improve we do not learn effectively from past incidents (Elliott and Smith 2006). As such it is no surprise that crowd related disasters continue to occur and as Santayana pointed out many years ago, ‘those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.’ (1905, p.284). A brief flick through the history of crowd disasters across the world will support this analysis with repeated proximate and distal causes identified.

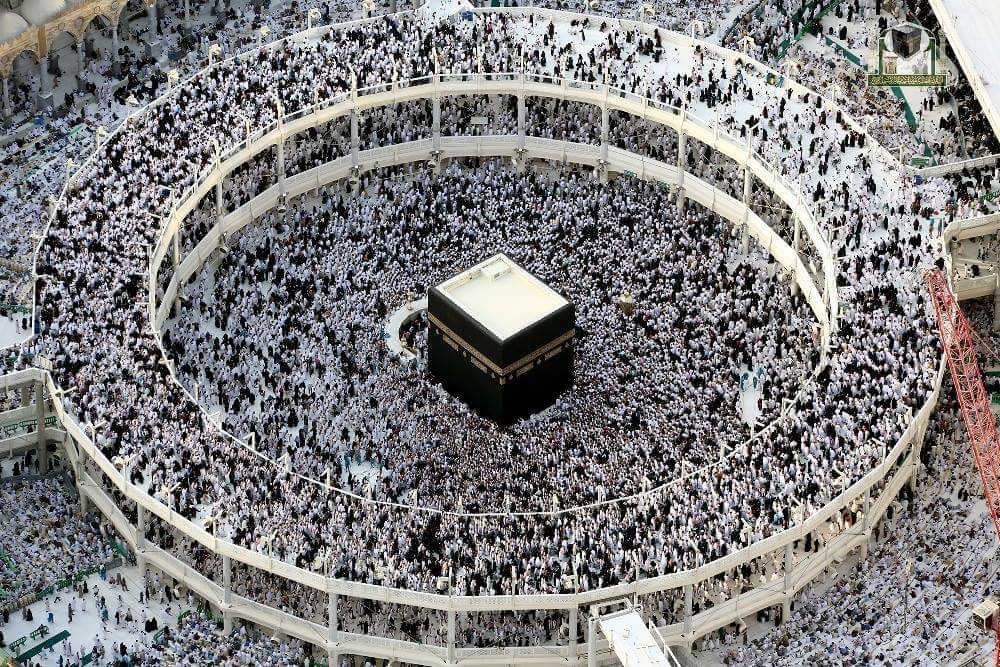

It is suggested, a key issue in the identifying and highlighting of these causes is that they are confined to the papers of inquiries and the conversations of experts whilst all too often the mainstream reporting of incidents focuses heavily on ‘the crowd’. Common terminology such as ‘mass panic’, ‘stampede’ and ‘out of control’ identify the behaviour of the crowd as the cause of disaster and this is very unhelpful in achieving the Cabinet Office crucial requirement to learn from past incidents (Helbing and Mukerji 2012, The Guardian 2008, Ranieri 2005, Cocking, Drury and Reicher 2007, Cabinet Office 2009).

Two reasons are proposed for the repeated blaming of the crowd; Firstly, classical theory (Le Bon 1895, McDougall 1920 and Freud 1922 for example) created a perception of crowds as a mad, impulsive, ignorant mob whereby personal inhibitions are masked and an individual is compared to a grain of sand which can be stirred up at will (Le Bon, 1895). The process of confirmation bias continues to strengthen this view following each crowd disaster with media reports simply feeding the narrative. Secondly, other potential culprits are able to defend their interests whilst the ‘crowd’ are often a faceless suspect without a spokesperson (Seabrook 2011)

With each passing disaster the behaviour of the crowd is regularly offered and accepted as a main cause, thus further reaffirming this position, and so the cycle continues. Helbing and Mukerji draw the following, accurate conclusion from this,

“Such views tend to blame the crowd for the disaster rather than drawing suitable consequences regarding the organization of mass events, the crowd management and communication. Therefore, recurring disasters may be a consequence of misconceptions about them.” (2012, p. 27)

Crowds are rarely irrational and as Still poignantly argues, ‘people don’t die because they panic, they panic because they are dying’ (Still cited Benedictus 2015). The acceptance of crowd behaviour as the key contributor to a disaster can stifle development in this field. Instead a more considered review of proximate and distal causes should be undertaken allowing for appropriate categorisation and in turn lessons learnt.